Про жанр "експплуатейшн" у кіно.

Exploiting Exploitation Cinema: an Introduction

David Roche

Texte intégral

- 1 For instance, one fan’s blog speaks of “[t]he exploitation genre” (See <http://popcornhorror.com/exploitation-film> accessed on 2/25/2016). Ano</http> (...)

- 2 The semantic refers to “linguistic meaning, i.e., the meaning in the dictionary, the syntactic to “ (...)

1What

is exploitation cinema? Exploitation cinema is not a genre; it is an

industry with a specific mode of production. Exploitation films are made

cheap for easy profit. “Easy” because they are almost always genre

films relying on time-tried formulas (horror, thillers, biker movies,

surfer movies, women-in-prison films, martial arts, subgenres like gore,

rape-revenge, slashers, nazisploitation, etc.). “Easy” because they

offer audiences what they can’t get elsewhere: sex, violence and taboo

topics. “Easy” because they have long targetted what has since become

the largest demographic group of moviegoers: the 15-25 age group

(Thompson and Bordwell, 310, 666). The exploitation film is not a genre,

and yet it is often described as such.1

This is, no doubt, because these movies do, as a group, share common

semantic, syntactic and pragmatic elements that, for Rick Altman, make

up the “complex situation” that is a film genre (Altman, 84).2

Semantic characteristics include excessive images of sex and violence,

bad acting, poor cinematography and sound; syntactic characteristics

include taboo themes, and flat characters or basic character arcs.

Evidently, these can mainly be put down to the mode of production. The

arguments for considering the exploitation film as a genre are, then,

mainly pragmatic: fans and critics often speak of the “exploitation

film” as if to designate a specific genre. That these movies have often

been exhibited in similar venues—grindhouses, drive-ins and today

direct-to-DVD—reinforces their commonality. Exploitation is not a genre,

then, but a label.

2Cinephiles,

film critics (Ken Knight, Richard Meyers) and scholars (Pam Cook,

Thomas Doherty) tend to associate exploitation cinema with a specific

period: the late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. For Doherty, exploitation

cinema as we know it emerged in the 1950s with the advent of low-budget

teenpics. In the mid-1940s, exploitation designated “films with some

timely or currently controversial subject which [could] be exploited,

capitalized on, in publicity and advertising”; the A-feature The Pride of the Yankees

(Samuel Goldwyn / RKO, Sam Wood, 1942) is one such example (Doherty,

6), though one could argue that producer Darryl Zanuck’s taste for the

“headline type of title story” was already exploitative in that sense

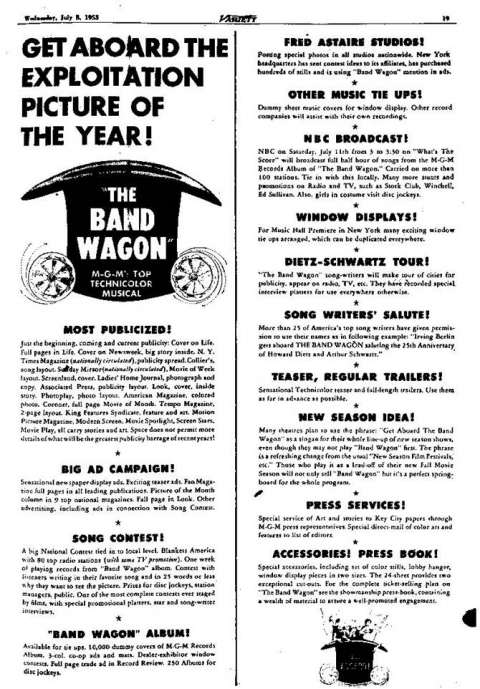

(Bourget, 99). In 1953, still, a musical like The Band Wagon

(MGM, Vincente Minnelli), as Sheldon Hall kindly pointed out to me in an

email, could be promoted as “the exploitation picture of the year”

simply because it promised to be highly successful [Fig. 1]. So it

wasn’t until the mid-1950s that “exploitation” came to mean both “timely

and sensational,” and came to have such a “bad reputation” (Doherty, 7).

3Both Felicia Feaster and Brett Wood’s Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Film

and Eric Schaefer’s “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!” A History of

Exploitation Films trace the history of exploitation cinema even further

back by examining a body of lesser known films of the 1920s-1950s that

Schaefer calls classical exploitation films. The emergence of this

industry on the margins of the U.S. film industry filled a vacancy left

by the latter in the 1910s. With Hollywood desperately trying to improve

its image (the Thirteen Points were issued in 1921), studios like

Universal and Triangle stopped making films about sex hygiene and the

white slave trade; the enforcement of self-censorship, with the Don’ts

and Be Carefuls of 1927 and the Production Code of 1930, confirmed that

imagery and narratives involving sexuality, homosexuality, drug use and

miscegenation were inappropriate. Exploiteers thus stepped in to profit

from an existing market for sex hygiene films, drug films, vice, exotic

and atrocity films, and nudist and burlesque films. With the exception

of burlesque, all these genres were meant to be simultaneously

sensational and educational, some of the sex hygiene films having been

solicited by the state or army (Schaefer, 27-28). Posters promised

nudity and often stressed the topicality of the film by drawing on

headlines, using words like “exposé” and “story” and asking questions

audiences would expect the film to answer (Schaefer, 106-9, 114) [Fig.

2]. Because of their emphasis on spectacle rather than on narrative,

these films, Schaefer argues, owed more to the “cinema of attractions”

of early silent cinema, as analyzed by Tom Gunning (2004) (Schaefer,

38). Thus, “the classical exploitation film was a form firmly rooted in

modes of representation, financing, production, distribution, and

ideology left behind by the mainstream movie industry after WW1”

(Schaefer, 41). Indeed, these films changed very little from the 1920s

to the 1950s and could sometimes be re-released with a new poster and

title as long as ten years after their initial release—this was the case

of Midnight Lady (Chesterfield, Richard Thorpe, 1932), re-released as

Secret of the Female Sex, and of Polygamy (Unusual Pictures, Pat

Carlyle, 1936), re-released as both Illegal Wives and Child Marriage

(Schaefer, 59-60). The ballyhoo surrounding the event was instrumental

in drawing audiences: exploiteers suggested local displays, sold themed

books, included nurses and strippers, and invited so-called specialists

to give lectures (Schaefer, 118, 126-27). Audiences probably saw these

movies just as much to learn about shameful taboo subjects as to enjoy

the sexual titillation and carnivalesque atmosphere of the show: they

“were encouraged to look on their attendance at an exploitation film as

an experience with multiple dimensions, one that would arouse, thrill,

entertain, and educate” (Schaefer, 110).

4Schaefer

attributes the disappearance of classical exploitation cinema both to

the retirement and death of the first generation exploiteers, and to the

fact that the Hollywood industry, because of competition from

television, increasingly explored forbidden topics in order to draw a

more mature audience (Schaefer, 326-37). Classical exploitation made way

for sexploitation. Historically, there are some connections between the

two. Russ Meyer was initially asked to make a classical exploitation

nudist film when he directed The Immoral Mr. Teas, which

Schaefer considers to have largely contributed to initiating

sexploitation (Schaeffer, 338). And the infamous Edward D. Wood, Jr.

launched his career with Glen or Glenda (1953), a movie about

tranvestites that retains the educational intent of classical

exploitation [Fig. 3], before moving on to horror (Bride of the Monster, 1955; Plan 9 from Outer Space, 1959) and sexploitation (Nympho Cycler,

1971). But sexploitation distinguished itself from its predecessor

because it had no claim to educate and adopted an ironic tone:

Sexploitation films can best be described as exploitation movies that focused on nudity, sexual situations, and simulated (i.e., nonexplicit) sex acts, designed for titillation and entertainment. Such films no longer required explicit education justification for presenting sexual spectacle on the screen—although they often made claims of social or artistic merit as a strategy for legal protection. (Schaefer, 338)

5The

pictures made by Allied Artists, DCA, Howco and AIP (American

International Pictures) have, Schaefer argues, more in common with the

B-movies the Hollywood industry stopped making in the 1950s (Schaefer,

330-31), namely that they are narrative films. So like their

predecessors, the new exploitation films filled a vacancy within the

mainstream industry.

6They

also testified to the industry’s growing awareness of the significance

of the youth market. In the 1950s, consumer society started not only to

target teenagers directly, but attempted to address them differently;

teenage advice books, for instance, were no longer written from the

superior perspective of the parent or teacher, but provided insight on

how to become popular at school (Doherty, 47). In Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s,

Doherty links the rise of the exploitation teenpic to the opportunity

to profit from the youth audience (Doherty, 12), either by creating

genres dealing with issues and topics they were interested in (the rebel

or rock’n’roll movie), or simply by integrating youthful characters in

pre-existing genres (like horror and sci-fi). With its hero who fails to

“adjust” and its gratuitous song and dance scenes, I Was a Teenage Werewolf (Sunset Productions, Gene Fowler, Jr., 1957), one of the top grossing films that year, does both (Fig. 4) (Doherty, 131).

Fig. 4

Advertisement for I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957)

Public domain

As a production strategy, the 1950s exploitation formula typically had three elements: (1) controversial, bizarre, or timely subject matter amenable to wild promotion (‘exploitation’ potential in its original sense); (2) a substandard budget; and (3) a teenage audience. Movies of this ilk are triply exploitative, simultaneously exploiting sensational happenings (for story value), their notoriety (for publicity value), and their teenage participants (for box office value). (Doherty, 7)

7In

spite of these differences—the target audience, the educational claims

or lack thereof, the emphasis on spectacle or narrative—the North

American exploitation film has always addressed topical issues and

resorted to exploitative images snubbed by the mainstream industry in

order to exploit the concerns of a specific market. In a sense, the

overt topicality of classical exploitation cinema made way, in

sexploitation, to more diffuse but just as pregnant themes, while I Was a Teenage Werewolf and The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

(Vortex, Tobe Hooper, 1974) prove that the tabloid title remained

effective. Moreover, one of the main strategies Schaefer identifies in

classical exploitation cinema—the recycling of stock footage or images

from previous films—was just as central to later exploitation films

(Schaeffer, 56-57). Clearly, exploiting exploitation cinema entails not

only the economic exploitation of an audience and subject matter, though

it is its primary concern, but also the repeated exploitation of the

form: in both cases, this exploitation is deliberately excessive in

order to make up for its (chiefly economic) lacks, and it is, I would

argue, in its excesses that potential disruption of the mainstream lies.

8I

started by noting that the use-value of the “exploitation film” is the

main reason it is sometimes considered as a genre. It is, in fact, the

“uses” made of exploitation cinema that will concern us here. As Pam

Cook has noted,

There is also a challenge for film-makers in the necessity of shooting fast and cheaply, in displaying ingenuity and in injecting ideas that do not entirely go along with hardcore exploitation principles. In other words, the director can also exploit the exploitation material in his or her own interests, and have fun at the expense of the genre. (Cook, 57)

The paradox of

“exploit[ing] the exploitation material in his or her own interests” is,

in effect, at the heart of many of the political and ethical

ambiguities that this issue will draw attention to. We aim to explore

the extent to which specific filmmakers, producers, actors and viewers

have exploited exploitation cinema as both an industry and a cinematic

form characterized by high economic constraints and, at least in some

respects, by a greater degree of latitude because of the necessity to

display taboo imagery and topics. In other words, to what extent do some

filmmakers and screenwriters turn the necessity to exploit

transgressive material into an opportunity to produce a subversive

subtext and/or aesthetics, one that challenges dominant and potentially

oppressive discourses and practices?

*

**

**

- 3 In Roy Frumkes’s documentary Document of the Dead (1985), producer Richard P. Rubinsten explains th (...)

9Before

the rise of the film school generation of the 1960s and 1970s, the

exploitation industry was a viable training ground for many filmmakers

and actors. Director/producer Roger Corman was to boast the “discovery”

of many of the big names of the period. His company, Filmgroup

Productions, founded in 1959, distributed the first movies starring Jack

Nicholson—The Wild Ride (Harvey Berman) and The Little Shop of Horrors (Roger Corman), both released in 1960—and produced Dementia 13 (1963) [Fig. 5], written and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, who had started out making nudie pics (The Bellboy and the Playgirls,

Defin Film/Rapid Film/Screen Rite Picture Company, 1962). As a producer

and director for AIP, founded in 1954, Corman cast Robert De Niro in

his own Bloody Mama (1970), one of the actor’s first parts, and produced Martin Scorsese’s second feature film, Boxcar Bertha, in 1972, and Brian De Palma’s Sisters in 1973. With New World Pictures, which Corman founded in 1970, he launched the careers of Joe Dante (Piranha, 1978), Jonathan Demme (Crazy Mama, 1975) and Jonathan Kaplan (Night Call Nurses,

1972). AIP and New World Pictures were the major players of U.S.

exploitation cinema, also producing some of the most successful

blaxploitation films, Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974), both starring Pam Grier and directed by Jack Hill, and distributing exploitation fare from Australia (Mad Max, George Miller, 1979), Canada (The House by the Lake, William Fruet, 1976), Sweden (Thriller,

Bo Arne Vibenius, 1973), Italy (the films of Mario Bava), Japan (the

Godzilla movies of the 1960s and 1970s) and Great Britain (many Hammer

films of the late 1960s and 1970s). The exploitation industry also

provided opportunities for women directors like Stephanie Rothman,

“produc[ing] some fascinating feminist films, which remain relevant”

(Cook, 64). Many of these exploitation films have retrospectively gained

a legitimacy they lacked upon release because fans and critics now view

them not just as exploitation films, but as early works evidencing the

talent and sometimes even personal signatures of major actors and

directors. In short, they have been salvaged by auteur theory, which has

long been integrated in both production,3

marketing and cinephile practices (Saper, 35; Verevis, 9-10; Roche,

2014, 13). Most of the articles in this issue confirm this trend by

recuperating auteurism to study specific filmmakers.

- 4 Baadasssss Cinema. Dir. Isaac Julien. Independent Film Channel, 2002.

- 5 Thompson and Bordwell include companies like AIP and NWP and directors like Meyer and Romero in ind (...)

10The

transformation of some exploitation films into auteur films was

facilitated by the fact that many were independently produced. Fourteen

of Russ Meyer’s films—from The Naked Camera (1961) to Cherry, Harry & Raquel!

(1970)—were produced and distributed by Eve Productions, co-owned by

his wife. David F. Friedman and Herschell Gordon Lewis founded their own

company to produce Blood Feast (1963) and 2,000 Maniacs! (1964), as did George A. Romero for Night of the Living Dead (1968), and Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974). Wes Craven’s debut The Last House on the Left

(1972) was produced by his friend Sean S. Cunningham’s company. And

unlike many of the blaxploitation films that imitated it and that were

produced by exploitation companies like AIP and sometimes even by major

studios (MGM for Shaft, Gordon Parks, 1971), Melvyn Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song

(1971) was produced by the director himself who sought to arouse the

interest of African American investors (most famously Bill Cosby).4

These films were then distributed by companies specialized in

exploitation and sometimes pornography (Bryanston Distributing, which

distributed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, had distributed the hit Deep Throat

in 1972). Though usually not directly associated with exploitation

cinema, John Waters operated very much like the exploiteers of classical

exploitation cinema (Feaster and Wood, 194-95), as Elise Pereira-Nunes shows in this issue, producing and distributing three films from Pink Flamingos (1972) to Desperate Living

(1977) through his company, Saliva Films. Many of the exploitation

films of the period that have since garnered the recognition of fans,

critics and scholars are, in fact, independent films.5

- 6 Wes Craven was directly involved in the New York avant-garde (Becker, 44).

- 7 Van Peebles has always denied the influence although he lived in France in the 1960. <http://www.culturopoing.com/cinema/entretien-avec-melvin-van-peebles/20090212> Accessed on F</http> (...)

11This

explains, at least in part, the relative freedom the filmmakers had to

experiment artistically and sometimes to ground exploitative imagery in

radical political subtexts. In the early 1970s, many filmmakers

integrated techniques initiated by the French Nouvelle Vague and/or

1960s underground cinema.6 Pam Cook notes that the “drug-induced fantasy scenes” in Rothman’s The Student Nurses

(New World Pictures, 1970) are “more in line with European art cinema

than the rough and ready codes of exploitation” (59) [41:01-45:10;

61:23-62:22]. Sweet Sweetback’s contains many scenes edited in

jump-cut (when a white cop fires at Sweetback on a bridge

[70:30-70:58]), a scene with the hero running that utilizes the split

screen technique to portray a character trapped by the city and the

police [64:47-65:34], and ends on a freeze frame of the hills where the

black man is now lurking [96:04], recalling the end of another ode to

rebellion, François Truffaut’s Les quatre cent coups (1959).7 Waters’s Female Trouble

(1974) similarly ends on a freeze frame of Dawn Davenport’s distorted

face as she thanks her wonderful fans while being electrocuted on the

electric chair [96:37]. Coming from the underground movement (Muir, 90),

the penultimate scene of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the mad

dinner party, orchestrates an escalation of extreme closeups of the

victim’s (Sally Hardesty’s) face edited in jump-cuts [74:50-76:40]

(Thoret, 73; Roche, 2014, 200), so that, unlike the famous shower scene

in Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) which also utilizes jump-cuts, the

editing does not mimic the physical violence (no one is stabbing her

yet) but effects the psychological violence of the scene; the sense of

anxiety that permeates the film is forcibly rendered by the physicality

of the concrete music score, composed and performed by Wayne Bell and

Hooper himself (Roche, 2014, 191-201). Filmmakers could also play with

generic conventions. Pam Cook argues that exploitation films “parody

rather than emulate” the mainstream productions they exploit (56). This

explains the ironic tone noted by Schaefer that can then be negotiated

from a camp perspective. In his analysis of The Toolbox Murders (Dennis Donnelly, 1978) included in this issue (“Unnatural, unnatural, unnatural, unnatural unnatural” . . . but real? The Toolbox Murders and the Exploitation of True Story Adaptations”), Wickham Clayton

analyzes the consequences of Donnelly’s placing the famous “based on a

true story” trope of exploitation horror at the end of the film, unlike

the famous opening carton of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre; here, the exploitative claim to timeliness provides an excuse for both the film’s ambiguous polics and incoherent narrative.

- 8 Critics like Sumiko Higashi (1990) and Tony Williams feel that the “grainy black-and-white still im (...)

12Early

defenders of independent horror of the 1970s, however, were mainly

interested in its political potential. Robin Wood famously stated that

it became “in the 70s the most important of all American genres and

perhaps the most progressive, even in its overt nihilism—in a period of

extreme cultural crisis and disintegration, which alone offers the

possibility of radical change and rebuilding” (76). As a Marxist and gay

activist, Wood was interested in how films like The Texas Chain Saw Massacre

attacked capitalist patriarchy (Wood, 82; Williams, 2014, 188, 194).

North American horror films of the 1970s have often been said to reflect

or address some of the cultural anxieties of the time, including the

Vietnam War, the state of the economy, the civil rights movement and the

women’s movement (Waller, 12; Worland, 231; Roche, 2014, 28). A

director like Wes Craven encouraged this reading of the violence of his

first film The Last House on the Left as an expression of “the

newsreel footage of the American carnage in Vietnam playing on

television every night” (Robb, 24), a sort of way to “bring the war

home,” as the slogan went. Canadian director Bob Clark’s Dead of Night (aka Deathdream,

1974) tells the story of a Vietnam veteran who, on his return home,

becomes a ghoul addicted to violence, his monstrosity clearly operating

as a metaphor for PTSD. If Romero discouraged reading Vietnam into Night of the Living Dead (Fig. 6),8 his fourth film, The Crazies

(1973), which depicts a military quarantine in a small town turning

into a fascist regime, relies on imagery of guerilla warfare and human

bonfires (like the monks in 1963) that audiences would have associated

with the war [47:42-50:29].

- 9 This is equally true of the Australian film The Cars That Ate Paris (Peter Weir, 1974), which deliv (...)

13Romero’s second zombie movie, Dawn of the Dead

(1978), set in a mall, delivers a critique of consumer society, the

line between the living and the dead appearing increasingly thin as both

have internalized the drive to consume (Williams, 2015, 91). Canadian

filmmaker David Cronenberg had previously recycled Romero’s zombie

imagery in order to assault the capitalist structures—the apartment

building in Shivers (1975), the clinic in Rabid (1977)—that repress basic drives and thus fashion the subject into a consuming body (Roche, 2006, 165-70). In The Texas Chain Saw Massacre,

the cannibal family’s economic status—several members have lost their

jobs while others operate a gas station that is out of gas—is a

synecdoche for the nation in which energy is lacking, and yet the

cannibals are driven to waste energy in their pursuit and destruction of

human bodies (Roche, 2014, 22-24). All these films exploit the taboo of

cannibalism as a perversion of consumerism, its most quintessential

expression, and contain it within a microcosm (a family house) that

metonymically represents the macrocosm (U.S. society).9

The paradox in this political exploitation of exploitation cinema is,

of course, that it critiques the economic system that sustains those

very films that are, above all, made to be exploited.

14The

subtexts of these particular films are exceptionally coherent, yet this

is not the case of the majority of exploitation films whose politics

are far more ambiguous. Nowhere is this more patent than in the

portrayal of female characters and the treatment of race, sexuality and

gender. The most obvious and famous example is probably Russ Meyer’s Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

(1965), which exploits a trio of bombshell pinups twofold by

fetishizing their bodies and depicting their sadistic violence on

normative society (the couple, the family), an attitude that is later

justified by the patriarchal family that legitimizes rape. In the end,

order is restored, as Linda avenges her previous boyfriend (Tommy) and

saves her new one (Kirk) by slaying Varla.

15Cook claims that

many of these films were made in response to public demand for more woman characters, and Jack Hill’s The Big Doll House (1971), or Joe Viola’s The Hot Box (1972), celebrated a popular version of “Women’s Lib”. In spite of the potential here for more active roles for women, these sexual role-reversal films generally cast super-aggressive women as mirror-images of men, without questioning those images too much. (61)

- 10 Apparently, it was also Downe who “got real women bikers as actresses” (Quarles, 37).

She-Devils on Wheels (Herschell Gordon Lewis, 1968), which Kristina Pia Hofer’s “Exploitation Feminism: ‘Trashiness, Lo-Fidelity and Utopia in She-Devils on Wheels and Blood Orgy of the Leather Girls’”

analyzes in this issue, initially seems to prove Cook right: the bikers

“treat men like they’re slabs of meat” [7:30], have contests to

determine who will get first pick and reject members who want to commit

to a relationship [28:20-33:42]. That said, if the female characters

basically do unto men what they would do unto women, unlike Meyer’s

pussycats, the Maneaters form a heterogeneous group both in terms of

physique and social class (not, however, in terms of race), accepting a

newbie who rides a mere scooter! The characters’ bodies are not

fetishized—a shower curtain and towel are used to conceal Karen’s body

when she steps out of the shower [48:49]—only the male victims’ in gory

close-ups [43:24-48:48]. This utopian matriarchy is a microcosm in a

world of men (pointedly, they are the only female biker gang in the

film, they fight a male car gang for turf and the police is comprised of

men). The end of the film can be read as a reversal of Faster, Pussycat!,

as Karen gives up the possibility of founding a family and thus

integrating normative patriarchy to stay with her sisters [75:00]. The

film’s feminist potential, which the music reinforces, Hofer argues, is

an exemplary case of exploiting exploitation cinema, and may have

something to do with the female screenwriter’s (Allison Louise Downe)

appropriating man’s (Fred M. Sandy) highly original idea.10

16The Big Doll House

(Jack Hill, 1971) exploits a genre that has existed since the 1930s:

the women-in-prison film. These films seem to cater to the heterosexual

male fantasy of spying on women who are all alone, offering glimpses of

beautiful women taking showers and sharing close quarters. The film

shamelessly fetishizes the prisoners, keeping the promise in the title.

Some of the women pleasure themselves and each other in the shower

[31:20-37:22]. One of the main characters (Alcott), however, rejects

lesbian sex and prefers to perform for a male character (Fred) peeking

at them through a window. Fred, here, embodies a stand-in for the male

spectator. The irony is that he abandons the voyeuristic position when

the female character ceases to act as a passive performer and returns

his gaze. In other words, he is scared off by her desire to share in the

pleasure. Logically, then, the following scene has Alcott enacting the

male characters’ fantasy by trying to rape Fred in the storeroom,

demanding that he “get to work,” skip foreplay and that he “get it up or

[she]’ll cut it off.” Clearly, Alcott’s sexual assertiveness is

phallic, castrating, “masculine,” confirming Cook’s argument. Another

limitation to the film’s sexual politics is that lesbian sexuality is

typically imagined as a mere replica of heterosexuality: the character

of Grear, who calls her girlfriends “baby” and says she likes “being on

top” [7:43], mistreats them just as men mistreated her [22:25], almost

behaving like a pimp [64:15]. Yet The Big Doll House is more

ambiguous and hesitant in its gendered terms. The prison is first

presented as a matriarchy run by Miss Dietrich and her female guards;

patriarchy is soon introduced as the overarching frame when we find out

that Miss Dietrich works for Colonel Mendoza, a man who only comes to

watch the women get tortured. In the end, Mendoza turns out to be Miss

Dietrich in disguise. In other words, the sadistic male gaze was a

sadistic female gaze all along, a revelation foreshadowed by the

utilization of a POV shot when Lucian, the female guard, looks at her

victims through the bars [61:00-61:52]. Thus, four years before Laura

Mulvey’s famous “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” The Big Doll House

offers counter-examples to the equation between male and camera gaze,

replacing the “male” with the “masculine female.” The sensationalistic

exploitation of heterosexual male fantasies thus leads, quite

unexpectedly, to subvert the conventions of classical cinema.

17Jack Hill’s later and more famous films, Coffy and Foxy Brown, which exploited the success of Sweet Sweetback’s and Shaft,

are particularly ambiguous because their basic premises—a beautiful

black woman uses her body to get revenge—allow them to indulge in sex

and violence on a background of identity politics involving gender, race

and class. For one, the fetishization of the female body for the male

gaze is dramatized within the film as a strategy to manipulate the

diegetic viewer. In Coffy, for instance, the heroine’s body is

displayed in a slow frontal zoom-in when she undresses to seduce one of

her future victims, King George [38:20-38:59]. Typical of exploitation

cinema’s ambiguous politics is the all-girl fight scene [42:52-45:11].

To draw the attention of an Italian mafioso, Coffy starts a fight with a

group of white prostitutes, thus performing the racist stereotype of

the “wild animal” the white man desires. The scene inverts the outcome

of the mudfight scene in The Big Doll House, with the black

woman coming out victorious thanks to the razor blades concealed in her

afro. Yet this figure of beauty, power and cunning also enables the film

to cater to the audience’s desire for nudity, as she neutralizes her

opponents by tearing off their clothes. Foxy Brown is, in this

respect, far less exploitative: the brief glimpse of Foxy’s naked body

in the shadows in the opening scene turns out to be a false promise

[6:00-6:15], and the film systematically distinguishes scenes where Foxy

is performing the aptly named “Misty Cotton,” a racist and sexist

stereotype she has constructed to seduce her opponents (usually wearing a

wig and a sexy dress or gown) from scenes where she is herself (wearing

more casual clothes with her hair done in a afro or wrapped in a

turban). On the surface, Foxy Brown further develops the racial

politics when the heroine allies herself with a local group of Black

Panthers; in the scenes where she visits their headquarters, Foxy is

even framed with portraits of Angela Davis in the background to

underline the physical likeness [73:31-74:10]. Yet I would argue that

this only serves to reinforce the divide between black and white in a

manner typical of blaxploitation. Indeed, the representation of the

criminal world in Coffy is more complex as a site of

intersectionality between gender, race and class: Coffy’s journey takes

her from a black pimp to the Italian mafia to a black politician,

confirming what her friend Cater, a black policeman, had told her from

the outset [11:56]. On this level, at least, Foxy Brown’s increased coherence diminishes the film’s political potential.

*

**

**

- 11 These are nonetheless based on homophobic stereotypes. In Blacula (AIP, William Crain, 1972), for i (...)

18We

have already noted that a few exploitation films have been acknowledged

as promising works or even masterpieces through auteur theory, even

when the movie happens to be by far a director’s crowning achievement

(this is clearly the case of Tobe Hooper and even, to some, of Wes

Craven). But it is, no doubt, the ambivalent politics of the

exploitation films of the 1960s and 1970s, combined with the ironic tone

noted by Schaeffer, that explains, at least in part, why many still

enjoy cult standing today. If these movies often targeted young

heterosexual rural white males, the audiences for these films have

diversified. As Anne Crémieux explains in this issue in

“Exploitation Cinema and the Lesbian Imagination,” some of these films,

in spite of their predominantly sexist and homophobic attitudes, have

been recuperated by contemporary LGBT audiences for whom negative

representations are less problematic than they were in the 1960s and

1970s. Members of these communities single out specific moments for

celebration. At festivals notably, audiences can negotiate images of

strong women, lesbian and (albeit less frequent) gay characters from a

camp perspective.11

This is especially true of lesbian communities who can tap into an

abundance of fantasies initially tailored for young heterosexual

males—Michelle Johnson’s Triple X Selects: The Best of Lezsploitation (2007) even tries to salvage the Canadian nazisploitation Ilsa: She Wolf of the SS

(Don Edmonds, 1975)! Thus, one of the pleasures provided by

exploitation cinema is akin to that provided by genre films: audiences

often seek in them “an increasingly intense counter-cultural genre

pleasure” which then “create[s] an invisible bond among fans of the same

genre” (Altman, 155, 165).

- 12 See Richard Dyer (1992).

19Some

of these fans went on to make films. The tradition of low budget

exploitation continued well into the 1980s, as Kristina Pia Hofer’s

piece on Blood Orgy of the Leather Girls (Michael Lucas, 1988) shows. TV shows like Charlie’s Angels (ABC, 1976-1981), Crémieux points out, bear the influence of the strong female characters of exploitation cinema. The Rocky Horror Picture Show

(Twentieth Century-Fox, Jim Sharman, 1975) taps into both the

transgressive potential of exploitation horror and the utopian potential

of the musical12

to propose a world free from oppressive heteronormalcy. An early

example of a fan of exploitation cinema exploiting his influences in a

very personal way is, no doubt, John Waters. Elise Pereira-Nunes’s “Sex,

Gore and Provocation: the Influence of Exploitation in John Waters’s

Early Films” shows how he appropriated imagery from the nudies pics of

Russ Meyer, the gore movies of Herschell Gordon Lewis and the Mondo Film

tradition from Italy in his films of the 1960s and 1970s. Each

influence operates on a specific level in terms of politics: the

subversion of gender and sexual identity, by modeling the persona of

Divine on Meyer’s bombshells, and the implication that Americans are

essentially primal animals like any other. More generally, celebrating

these lower forms is, of course, a provocative act in itself and largely

participates in the assault on propriety that is at the basis of

Waters’s aesthetics, an aesthetics which appealed to student and gay

audiences of the 1970s and contributed to the emergence of a camp

sensitivity.

20Exploitation

films of the 1950s-1970s have also had a direct influence on the films

of contemporary American filmmakers, including two of the most famous:

Tim Burton and Quentin Tarantino. The imagery we often describe as

Burtonian is a mix of Disney animation, the classic monster movies of

the 1930s, and exploitation horror and scifi of the 1950s-1970s. The

presence of Vincent Price in the short film Vincent (1982) and Edward Scissorhands

(1990) pays tribute to the films of Roger Corman, while specific

shots—the low-angle establishing shots of the Inventor’s castle [4:30,

8:55] or the high-angle shot of artificial hands [81:30] in Edward Scissorhands

(1990), the medium closeup of the Corpse Bride unveiling her face in

the 2005 film [16:30]—cite, as Sarah Hameau (2015) has noted, The Curse of Frankenstein

(Hammer Films, Terrence Fisher, 1957). I would argue that Burton’s

integrating exploitation imagery and material in mainstream films is, in

effect, an aesthetic project with political implications: it celebrates

the “lower” form by evincing its poetry. This project is notably

carried out across three films made back to back: Ed Wood (1994) is a celebration of the creative energy of the man who is said to have made the worst movie of all time, Mars Attacks! (1996), a parody of 1950s scifi like Invasion of the Saucer Men (AIP, Edward L. Cahn, 1957) and a political satire of the 1990s U.S.; Sleepy Hollow (1999), both a remake of Disney’s 1949 adaptation and Burton’s “love letter to Hammer, Corman’s Pit and the Pendulum (1961), and Mario Bava’s neo-baroque La maschera del demonio (The Mask of Satan, 1960)” (Carver, 121).

21Tarantino’s

project is similar to Burton’s but more radical insofar as his films

celebrate lower forms that have yet to be redeemed. Like Burton, he

refers to exploitation cinema by casting actors associated with it (Pam

Grier, David Carradine), recycling specific characters (Pai Mei in Kill Bill Vol. 2, 2004), citing specific motifs (in Kill Bill, Elle Driver wears an eye patch like Frigga, the heroine of the Swedish rape-revenge film Thriller,

Bo Arne Vibenius, 1973), and using music from Italian exploitation

films (often composed by Ennio Morricone). In his article for this issue

entitled “Quentin Tarantino : du cinéma d’exploitation au cinéma” Philippe Ortoli

argues that Tarantino’s exploitation of exploitation cinema is not just

fannish; it is grounded in a view of art as repetition with difference,

which, in Django Unchained (2012), is incarnated in the

exchange between Django and the character of Franco Nero, the original

Django of 1966 who spawned a host of others: exploitation cinema, a form

founded on the recycling of spectacular images, would thus epitomize

this view. Tarantino’s approach is more comprehensive not only because

he taps into exploitation cinema on an international level and across

various genres (Italian Westerns, martial arts movies), but also because

it explores the political ambiguities of exploitation cinema Burton

tends to ignore. This is most obvious in Jackie Brown (1997) and Death Proof

(2007). The first is a critical homage to blaxploitation that

simultaneously invokes blaxploitation (via Grier, Ordell Robbie’s look

and the music Roy Ayers composed for Coffy) and

counters the ambiguous politics of these films by making Jackie a strong

woman who achieves her goals without resorting to sex and

self-fetishization; by portraying an interracial romance, Tarantino’s

film also rejects what Crémieux calls “the schism between blacks vs.

whites” blaxploitation films antagonized. As the second part of Grindhouse, Death Proof

invokes one of the modes of exhibition of exploitation cinema, but the

film proposes to revisit various exploitation genres (the slasher,

rape-revenge, the car movie) through the prism of feminist film theory:

in so doing, it reveals that generic conventions are gendered, and thus

that subverting these conventions can potentially deconstruct binaries

like “male”/“female” and “masculine”/“feminine,” revealing them to be

constructs (Roche, 2010); the scene where Stuntman Mike takes pictures

of the girls in the airport parking lot, in particular, undermines the

Mulveyan equation of male gaze by opposing image and sound, as the

music, “Unexpected Violence” (Morricone), is borrowed from The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, Dario Argento, 1970), a movie in which the stalker is a woman [65:33-66:31].

22Other filmmakers have basically followed Tarantino’s lead, especially in the horror genre. Directed by Robert Rodriguez, Planet Terror, the first part of Grindhouse,

is a zombie movie in the Romero tradition: the ensuing chaos reveals

how dysfunctional existing institutions (the army, science, the family)

are and ultimately promises a brave new world with Cherry Darling at its

center; the limitation, however, is that the matriarch’s power stems

from the phallic machine gun the hero (Wray) has endowed her with. Eli

Roth’s recent Knock, Knock (2015) falls into similar trappings,

as this inverted rape-revenge fantasy—Keanu Reeves gets raped by two

beautiful young women—seems to prove the sexist point that all men are

essentially the same (at least so far, as one of his tormentors says).

In other words, roles are reversed, but underlying structures are

maintained. Roth’s earlier films, Hostel I and II (2005, 2007),

pursue the critique of capitalism of 1970s exploitation horror while

retaining one of its main ambiguities, since “the film can be read as

the critique of its main selling point” (Ortoli, 437, my translation). Hostel II

is, in my opinion, more intelligent than the first installment, not so

much because it counters the sexism of the first by focusing on female

characters, but because the Final Girl survives by inverting the

villain/victim binary through capital: the film’s ultimate statement on

the state of global capitalism is that the only reason she survives is

that she can lay out more money than her oppressor; in other words,

capital, not the torture devices, is the real weapon of choice. Thus, Hostel I and II, Pierre Jailloux

argues in his article for this issue entitled “Quentin Tarantino : du

cinéma d’exploitation au cinéma,” dramatize how actual bodies and their

virtual images have become indistinguishable in a hyperreal globalized

world where reality has dissolved into images. The films, I would

contend, not only represent unlikely examples of Gilles Deleuze’s

“crystal-image,” i.e., an image for which it is impossible to tell the

actual image and its virtual image apart (Deleuze, 93-94), but they suggest that our “reality” has become a “crystal-image.”

23The

films of Rob Zombie also pursue the critique of the family and

capitalism of independent horror of the 1970s, but also seek to

rehabilitate the figure of the redneck by emphasizing their status as

social victims in American society and by eliminating racial oppositions

between black and white—through the friendship between Captain

Spaulding and Charlie Altamont in The Devil’s Rejects (2005).

In this respect, Zombie pursues the exploration of social class effected

in the films of Romero. His remake of John Carpenter’s Halloween

(1978) is particularly illuminating as a critique of the politics of

the original film, endowing the character of Michael Myers with a

pathology and celebrating the assertive sexuality of all the female

characters (Roche, 2014, 112-13). Zombie’s animation feature, The Haunted World of El Superbeasto (2009), as Pierre Floquet demonstrates in this issue in “The Haunted World of El Superbeasto:

An Animated Exploitation of Exploitation Cinema,” is perhaps less

coherent both in terms of politics and aesthetics. On the one hand,

Zombie mixes genres like Tarantino in Death Proof (in this

case, the wrestling movie, the zombie movie, nazisploitation, the biker

movie) and depicts a female superheroine (Suzi X) like Cherry Darling in

Planet Terror, but on the other, Zombie shamelessly fetishizes

Suzi X who ultimately serves to reinstate order. In the end, Zombie

fails to tap into the animation medium’s potential for flexible bodies

to subvert essentialist conceptions of the body. Rodriguez, Roth and

Zombie have in common that they are somewhat aware of the ambiguities of

the exploitative material they themselves exploit, but they do not

always succeed in consistently resolving these ambiguities, perhaps

because they remain fascinated with the spectacle itself, or perhaps

because these ambiguities remain as unresolvable as the paradox of

creating a consumer product that criticizes consumer society.

24In

any case, each article in this issue attempts to pinpoint and address

those very ambiguities and how they can be “used.” As I have attempted

to show in this introduction, these ambiguities can be viewed as

limitations imposed by the imperatives of exploitation cinema, but they

also have the potential to be appropriated by filmmakers and audiences

who, by recycling transgressive images, sounds and, more generally,

exploitation conventions, can make them resignify through irony, parody,

a camp sensitivity, sometimes all three, and can, in the process,

invent an aesthetic, personal or group identity founded on the practice

of recreation. It is this practice that can, in effect, be subversive

and contribute to changing the normative discourses and practices.

Exploiting exploitation cinema is not just about making money, learning

one’s craft or launching one’s career. It is a recognition that the

potentials within the constraints are endless because the industry and

form are founded on the very process of recycling. This, no doubt,

explains why the ambiguities of exploitation cinema remain even when

filmmakers and audiences strive to work through them. It also entails

that exploitation cinema, as Tarantino’s films suggest, is, by its very

excesses, the quintessence of cinema: both an industry and a medium

founded on recycling forms and images with variation.

Bibliographie

Des DOI (Digital Object Identifier) sont

automatiquement ajoutés aux références par Bilbo, l'outil d'annotation

bibliographique d'OpenEdition.

Les utilisateurs des institutions abonnées à l'un des programmes freemium d'OpenEdition peuvent télécharger les références bibliographiques pour lesquelles Bilbo a trouvé un DOI.

Les utilisateurs des institutions abonnées à l'un des programmes freemium d'OpenEdition peuvent télécharger les références bibliographiques pour lesquelles Bilbo a trouvé un DOI.

ALTMAN, Rick, Film/Genre, London, BFI, 1999.

BECKER, Matt, “A Point of Little Hope: Hippie Horror Films and the Politics of Ambivalence,” The Velvet Light Trap, vol. 57, Spring 2006, 42-59.

DOI : 10.1353/vlt.2006.0011

DOI : 10.1353/vlt.2006.0011

The Big Doll House. Dir. Jack Hill.

Written by Don Spencer. With Judith Brown (Collier), Roberta Colins

(Alcott), Pam Grier (Grear), Kathryn Loder (Lucian), Christiane

Schmidtmer (Miss Dietrich) and Pat Woodell (Bodine), New World Pictures,

1971, DVD, Bach Films, 2011.

BOURGET, Jean-Loup, Hollywood, la norme et la marge, Paris, Armand Colin, 2005 [1998].

CARVER, Stephen, “‘He wants to be just like

Vincent Price’: Influence and Intertext in the Gothic Films of Tim

Burton,” in WEINSTOCK, Jeffrey Andrew, ed., The Works of Tim Burton: Margins to Mainstream, New York and Basingstoke, UK, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013, 117-32.

Coffy, Written and directed by Jack

Hill, with Pam Grier (Coffy), Allan Arbus (Arturo Vitroni), Booker

Bradshaw (Howard Brunswick) and Robert DoQui (King George), American

International Pictures, 1973, DVD, MGM / United Artists, 2004.

COOK, Pam, “The Pleasures and Perils of Exploitation Films,” in Screening the Past: Memory and Nostalgia in Cinema, London and New York, Routledge, 2005, 52-64.

Corpse Bride, dir. Tim

Burton, written by John August, Caroline Thompson, and Pamela Pettler,

with Johnny Depp (Victor Van Dort) and Helena Bonham Carter (Emily),

Warner Bros Pictures, 2005, DVD, Warner Home Video, 2006.

The Crazies, directed by George A

Romero, written by Paul McCollough and George A. Romero, with Lane

Carroll (Judy), Will MacMillan (David) and Harold Wayne Jones (Clank),

Pittsburgh Films, 1973, DVD, Wild Side Video, 2006.

Death Proof, written and directed by

Quentin Tarantino, with Kurt Russell (Stuntman Mike), Vanessa Ferlito

(Arlene), Jordan Ladd (Shanna), Rose McGowan (Pam), Sydney Tamiia

Poitier (Jungle Julia), Zoë Bell (Zoë), Rosario Dawson (Abernathy),

Tracy Thoms (Kim) and Mary Elizabeth Winstead (Lee), Dimension Films /

Troublemaker Studios / Rodriguez International Pictures / The Weinstein

Company, 2007, DVD, TF1 Vidéo, 2007.

DELEUZE, Gilles, Cinéma 2 : L’Image-temps, Paris, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1985.

DOHERTY, Thomas, Teenagers and Teenpics: The Juvenilization of American Movies in the 1950s, Philadelphia, Temple UP, 2002.

DYER, Richard, “Entertainment and Utopia,” in DYER, Richard, ed., Only Entertainment, London, New York, Routledge, 1992, 17-34.

Edward Scissorhands, dir Tim Burton,

written by Caroline Thompson, with Johnny Depp (Edward), Winona Rider

(Kim), Dianne Wiest (Peg), Anthony Michael Hall (Jim), Vincent Price

(The old inventor), 20th Century Fox, 1990, DVD, 20th Century Fox, 2002.

FEASTER, Felicia and Bret WOOD, Forbidden Fruit: The Golden Age of the Exploitation Film, Parkville, MD, Midnight Marquee Press, 1999.

Female Trouble, written and directed

by John Waters, with Divine (Dawn Davenport / Earl Peterson), David

Lochary (Donald Dasher) and Mary Vivian Pearce (Donna Dasher),

Dreamland, 1974, DVD, Metropolitan Vidéo, 2006.

Foxy Brown, written and directed by

Jack Hill, with Pam Grier (Foxy Brown), Antonio Fargas (Link Brown),

Peter Brown (Steve Elias) and Karthyn Loder (Katherine Wall), American

International Pictures, 1974, DVD, MGM / United Artists, 2004.

GUNNING, Tom, “Now, You See It, Now You Don’t:

The Temporality of the Cinema of Attractions,” in GRIEVESON, Lee et

Peter KRÄMER, eds., The Silent Cinema Reader, London and New York, Routledge, 2004, 41-50.

HAMEAU, Sarah, “The Frankenstein Motif in Tim

Burton’s Film: (Recreation and Metafiction),” Mémoire de M2R, Université

Toulouse Jean Jaurès, 2015.

HIGASHI, Sumiko, “Night of the Living Dead: A

Horror Film about the Horrors of the Vietnam Era,” in DITTMAR, Linda

Dittmar and Gene MICHAUD, eds., From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film, New Brunswick, NJ, Rutgers UP, 1990, 175-88.

KNIGHT, Ken, The Midnight Grind: A Tribute to “Exploitation” Films of the 70s, 80s, and Beyond, Bloomington, IN, AuthorHouse, 2012.

MEYERS, Richard, For One Week Only: The World of Exploitation Films, Piscataway, NJ, New Century Publishers, 1983.

MUIR, John Kenneth, Eaten Alive at a Chainsaw Massacre: The Films of Tobe Hooper, Jefferson, NC and London, McFarland, 2002.

MULVEY, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975), in MULVEY, Laura, Visual Pleasure and Other Pleasures, Bloomington, Indianapolis, Indiana UP, 1989, 14-26.

DOI : 10.1093/screen/16.3.6

DOI : 10.1093/screen/16.3.6

NOVOTNY, Lawrence, “A Cinema of Contradictions:

Gay and Lesbian Representation in 1970s Blaxploitation Films,” in

ELLEDGE, Jim, ed., Queers in American Popular Culture, Volume 2, Santa Barbara, CA, Denver, CO, Oxford, UK, Praeger, 2010, 103-22.

Night of the Living Dead, written and

directed by George A. Romero, with Duane Jones (Ben), Judith O’Dea

(Barbra) and Karl Hardman (Harry), 1968, DVD, AML, 2006.

ORTOLI, Philippe, Le Musée imaginaire de Quentin Tarantino, Paris, Cerf-Corlet, 2012.

QUARLES, Mike, Down and Dirty: Hollywood’s Exploitation Filmmakerrs and Their Movies, Jefferson, NC, and London, McFarland, 1993.

RAYNER, Jonathan, “‘Terror Australis’: Areas of

Horror in the Australian Cinema,” in SCHNEIDER, Steven Jay Schneider

and Tony WILLIAMS, eds, Horror International, Detroit, MI, Wayne State UP, 2005, 98-113.

ROBB, Brian J., Screams & Nightmares: The Films of Wes Craven, Woodstock, NY, Overlook Press, 1998.

ROCHE, David, “David Cronenberg : une mission utopique,” in DUPERRAY, Max, Gilles MENEGALDO and Dominique Sipière, eds., Éclats du noir : gothique, fantastique et détection dans le livre et le film, Aix-en-Provence, Publications de Provence, 2006, 163-84.

---, “Quentin Tarantino’s Death Proof (2007): Subverting Gender through Genre or Vice Versa?” in DEL MAR AZCONA, María and Celestino DELEYTO, eds., in Generic Attractions: New Essays on Film Genre, Paris, Michel Houdiard, 2010, 337-53.

---. Making and Remaking Horror in the 1970s and 2000s: Why Don’t They Do It Like They Used To?, Jackson, MS, UP of Mississippi, 2014.

SAPER, Craig, “Artificial Auteurism and the

Political Economy of the Allen Smithee Case,” in BRADDOCK, Jeremey and

Stephen HOCK, eds., Directed by Allen Smithee, Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press, 2001, 29-49.

SCHAEFER, Eric, “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!” A History of Exploitation Films, 1919-1959, Durham, NC, Duke UP, 1999.

She-Devils on Wheels, dir. Herschell

Gordon Lewis, written by Allison Louise Downe, with Betty Connell

(Queen), Nancy Lee Noble (Honey Pot), Christie Wagner (Karen) and Rodney

Bedell (Ted), Mayflower Pictures, 1968, DVD, Image Entertainment, 2000.

The Student Nurses, dir. Stephanie

Rothman, written by Don Spencer, based on a story by Stephanie Rothman

and Charles S. Swartz. With Elain Giftos (Sharon), Karen Carlson

(Phred), Brioni Farrell (Lynn) and Barbara Leigh (Priscilla), New World

Pictures, 1970, DVD, New Concorde, 2003.

Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song,

written and directed by Melvin Van Peebles, with Melvyn Van Peebles

(Sweetback), Simon Chuckster (Beetle), Hubert Scales (Mu-Mu) and John

Dullaghan (Commissioner), Yeah, 1971, DVD, Arte Editions, 2003.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, dir.

Tobe Hooper, screenwriters: Kim Henkel and Tobe Hooper. With Marilyn

Burns (Sally Hardesty), Allen Danziger (Jerry), Gunnar Hansen

(Leatherface), Teri McMinn (Pam), Edwin Neal (Hitchhiker), Paul A.

Partain (Franklin Hardesty), Jim Siedow (Old Man or Cook) and William

Vail (Kirk), Vortex, 1974, DVD, Universal Pictures, 2003.

THOMPSON, Kristin and David BORDWELL, Film History: An Introduction, 3rd Edition, New York, McGraw Hill International Edition, 2010 [1994].

THORET, Jean-Baptiste, Une Expérience américaine du chaos : Massacre à la tronçonneuse de Tobe Hooper, Paris, Dreamland, 1999.

VEREVIS, Constantine, Film Remakes, Edinburgh, Edinburgh UP, 2006.

DOI : 10.1007/978-1-137-08168-1

DOI : 10.1007/978-1-137-08168-1

WALLER, Gregory A., ed, American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film, Urbana and Chicago, U of Illinois P, 1987.

WILLIAMS, Tony, Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film, Jackson, MS, UP of Mississippi, 2014 [1996].

---, Knight of the Living Dead: The Cinema of George A. Romero, London and New York, Wallflower Press, 2015 [2003].

WOOD, Robin. Hollywood: From Vietnam to Reagan . . . and Beyond, Expanded and revised edition, New York, Columbia UP, 2003 [1986].

WORLAND, Rick, The Horror Film: An Introduction, Malden, MA, and Oxford, UK, Blackwell, 2007.

Notes

1

For instance, one fan’s blog speaks of “[t]he exploitation genre” (See

<http://popcornhorror.com/exploitation-film> accessed on

2/25/2016). Another describes exploitation film as “[t]his film genre”

(See

<http://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/10-noteworthy-exploitation-films.htm>

accessed on 2/25/2016). The wikipedia page speaks of “this genre” (see

<https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exploitation_film> accessed on

2/25/2016).

2

The semantic refers to “linguistic meaning, i.e., the meaning in the

dictionary, the syntactic to “textual meaning,” i.e., meaning derived

from the structure. Semantic elements might be common topics, shared

plots, key scenes, character types, familiar objects or recognizable

shots and sounds,” while syntactic analysis focuses on “deeper

structures,” such as “plot structure, character relationships or image

and sound montage” (Altman, 79). Pragmatic analysis addresses the “use

factor” and “must constantly attend to the competition among multiple

users that characterizes genres” (Altman, 210).

3 In Roy Frumkes’s documentary Document of the Dead (1985), producer Richard P. Rubinsten explains that he and Romero functioned in a European fashion and followed auteur theory.

4 Baadasssss Cinema. Dir. Isaac Julien. Independent Film Channel, 2002.

5 Thompson and Bordwell include companies like AIP and NWP and directors like Meyer and Romero in independent cinema (491).

6 Wes Craven was directly involved in the New York avant-garde (Becker, 44).

7

Van Peebles has always denied the influence although he lived in France

in the 1960.

<http://www.culturopoing.com/cinema/entretien-avec-melvin-van-peebles/20090212>

Accessed on February 16, 2016.

8

Critics like Sumiko Higashi (1990) and Tony Williams feel that the

“grainy black-and-white still images” at the end of the film recall

photos of World War II concentration camps or Vietnam [89:17-95:38]

(Williams, 2015, 30).

9 This is equally true of the Australian film The Cars That Ate Paris

(Peter Weir, 1974), which delivers a “comic but unflinching critique of

capitalism and consumerism as cannibalism and murder” (Rayner, 102).

Its opening credits, like those of Shivers, resemble a commercial.

10 Apparently, it was also Downe who “got real women bikers as actresses” (Quarles, 37).

11 These are nonetheless based on homophobic stereotypes. In Blacula

(AIP, William Crain, 1972), for instance, the gay couple, Billy and

Bobby, are coded gay, notably because they talk with a lisp and are

incapable of defending themselves, and their death eliminates “a threat

to heteronormative masculine identity” (Novotny, 112-13).

12 See Richard Dyer (1992).

Haut de pageTable des illustrations

|

|

|---|---|

| Titre | Fig. 1 |

| Légende | Advertisement for The Band Wagon |

| Crédits | © Variety (July 1953) |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-1.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 156k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 2 |

| Légende | Advertisement from press book for The Desperate Women (1954) |

| Crédits | Public domain |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-2.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 204k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 3 |

| Légende | Poster of Glen or Glenda (1953) |

| Crédits | Public domain |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-3.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 152k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 4 |

| Légende | Advertisement for I Was a Teenage Werewolf and I Was a Teenage Frankenstein (1957) |

| Crédits | Public domain |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-4.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 132k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 5 |

| Légende | DVD cover Dementia 13 (1963) |

| Crédits | © Ovation Home Video |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-5.jpg |

| Fichier | image/jpeg, 136k |

|

|

| Titre | Fig. 6 |

| Légende | Screen grab from Night of the Living Dead (1968) |

| Crédits | Public domain |

| URL | http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/docannexe/image/7846/img-6.png |

| Fichier | image/png, 319k |

Pour citer cet article

Référence électronique

David Roche, « Exploiting Exploitation Cinema: an Introduction », Transatlantica [En ligne], 2 | 2015, mis en ligne le 14 juillet 2016, consulté le 28 mai 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/7846Haut de page

Auteur

David Roche

Université Toulouse Jean Jaurès, CAS

Articles du même auteur

-

Martine Beugnet, Allan Cameron and Arild Fetveit, eds., Indefinite Visions: Cinema and the Attractions of Uncertainty [Texte intégral]Paru dans Transatlantica, 2 | 2017

-

Gilles Menegaldo et Lauric Guillaud, dirs, Le Western et les mythes de l’Ouest : Littérature et arts de l’image [Texte intégral]Paru dans Transatlantica, 2 | 2016

-

Paru dans Transatlantica, 1 | 2016

-

Traduit de l’américain par Stan Cuesta, Paris, Rivages Rouge, 2014 [2013]Paru dans Transatlantica, 1 | 2015

-

Philippe Ortoli. Le Musée imaginaire de Quentin Tarantino [Texte intégral]Paru dans Transatlantica, 1 | 2014

-

Pertuis, Rouge Profond, 2013Paru dans Transatlantica, 1 | 2013https://journals.openedition.org/transatlantica/7846

Коментарі

Дописати коментар